Bipolar disorder stigma stems from lack of understanding

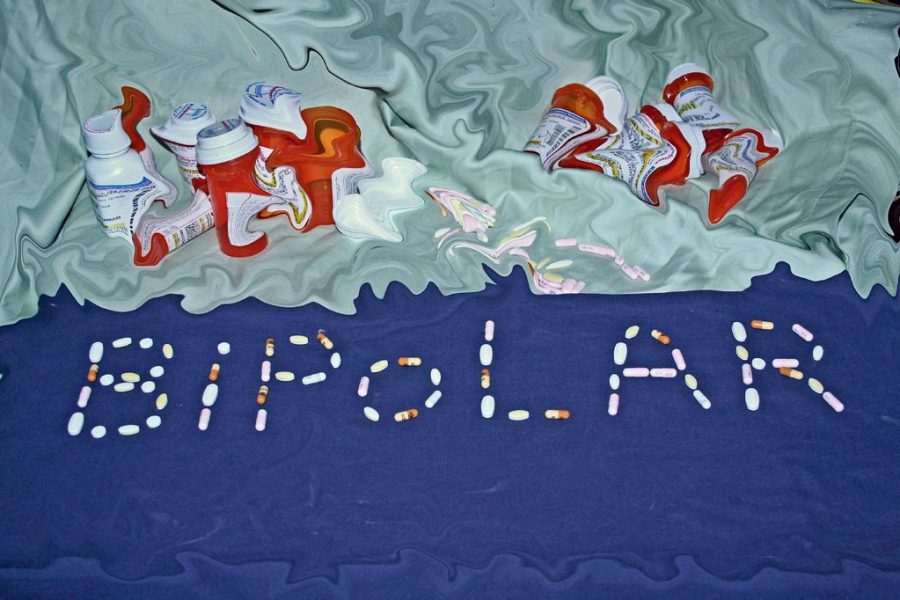

“In search for the right combination” by L.G.Mills

*Names changed for anonymity

Bipolar disorder is characterized by extreme shifts in mood. These shifts are often cyclical, including episodes of depression and mania lasting anywhere between hours and months. According to the Mayo Clinic, depressive episodes may include symptoms such as low energy, low motivation and loss of interest in daily activities, and manic episodes may include high energy, reduced need for sleep and loss of touch with reality.

Senior Amelia Faust* was recently diagnosed with bipolar disorder. According to Faust, depressive and manic episodes look different in different people and often manifest in unexpected ways.

“I have depressive episodes where I can’t get out of bed,” Faust said. “I don’t feel sad when I’m in a depressive state—I just don’t take care of myself well. I struggle to complete my homework.”

Like many other mental illnesses, diagnosis provides many benefits. It offers patients a new lens while opening up opportunities for treatment. But according to school psychologist Jennifer Zacharski, psychiatrists often shy away from diagnosing bipolar disorder. The similarities between depressive episodes and depression make misdiagnosis commonplace, especially among adolescents.

“I was originally diagnosed with depression,” Faust said. “I felt really hopeless because I was on medication that wasn’t helping me. I think that getting diagnosed properly and being put on the right medication made me feel more hopeful.”

There are two main subtypes of bipolar disorder: bipolar 1 and bipolar 2. Bipolar 1 involves more intense manic episodes, while bipolar 2 involves more frequent depressive episodes. Both subtypes are treated using similar methods: medication and therapy.

“The two main types of therapy are cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectic behavioral therapy,” Zacharski said. “Cognitive behavioral therapy gives you exercises to reframe and retrain your brain. Dialectic behavioral therapy teaches you how to make better decisions during stressful times.”

Bipolar disorder often impacts more than the person who has it—when left undiagnosed, its instability can affect close friends and family members as well. Sophomore Abigail Johanssen* grew up with a mother with bipolar disorder. According to Johanssen, her mother’s unstable moods prior to treatment influence her own perceptions and relationships.

“Your whole life, you see your parent as an example,” Johanssen said. “You see their behaviors and your relationship as normal, whether that is true or not. I think it definitely had an impact on me.”

Living with someone with bipolar disorder creates a unique set of implications. Zacharski encourages anyone who lives with someone with bipolar disorder to reach out to a counselor, therapist or school psychologist to gain a better understanding of these challenges.

“Your environment is unpredictable,” Zacharski said. “You should reach out to a clinician to help you reframe what’s going on with the person you love.”

According to Zacharski, when treated, those diagnosed with bipolar disorder can live without being significantly impacted by their disorder. Research and consulting with professionals when needed provides a better understanding—a key step toward removing stigma.

“I think that people assume bipolar disorder is way more impairing than anxiety or depression,” Johanssen said. “If people knew that, in reality, it’s not always as intense as they think, they would understand it better.”